Clubbing finger, also known as digital clubbing, is a medical condition characterized by the abnormal enlargement of the fingertips and changes in the nail beds. Often associated with various underlying health issues, clubbing can serve as a visible indicator of systemic diseases, particularly those affecting the lungs and heart. Recognizing and understanding this condition is vital for timely diagnosis and management, which can significantly impact patient outcomes. This article provides a comprehensive overview of clubbing finger, exploring its causes, symptoms, diagnostic methods, treatments, and preventive measures to promote awareness and early intervention.

Understanding Clubbing Finger: An Overview of the Condition

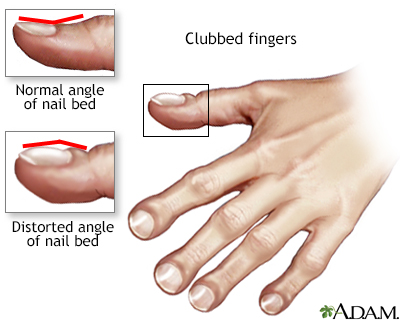

Clubbing finger manifests through a distinctive swelling of the fingertips, giving them a rounded, bulbous appearance. It is characterized by increased soft tissue proliferation beneath the nail beds, leading to a curved, convex shape of the nails and a loss of the normal angle between the nail and the nail bed. The condition can affect one or multiple fingers and may develop gradually over time. While the exact pathophysiology remains complex, it is believed to involve alterations in blood flow and tissue growth driven by underlying systemic issues. Recognizing the physical signs of clubbing is crucial for healthcare providers, as it often signals more serious health problems that require further investigation.

Clubbing is not a disease itself but a clinical sign associated with various medical conditions. It can be congenital, present from birth, or acquired later in life. Acquired clubbing is far more common and usually linked to chronic illnesses. The degree of clubbing can vary from mild to severe, with some patients experiencing only subtle changes while others have pronounced deformities. The evolution of clubbing typically correlates with the progression of the underlying disease, making it a valuable indicator for clinicians monitoring chronic conditions. Understanding these nuances helps in differentiating between benign and potentially life-threatening causes of the condition.

The physical examination of clubbing involves specific assessments, such as the Schamroth’s window test, where the nail beds are observed for the absence of a normal diamond-shaped window when the fingertips are placed together. Additional signs include a clubbing angle greater than 180 degrees, increased nail bed curvature, and soft tissue swelling. These observable features assist clinicians in diagnosing clubbing accurately. Moreover, the presence of clubbing warrants a thorough investigation to identify any underlying health issues, emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach to patient assessment.

Clubbing has been historically associated with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, but it can also be linked to gastrointestinal, infectious, and neoplastic conditions. Its presence often prompts further diagnostic workup to explore potential causes. In some cases, clubbing may be idiopathic, with no identifiable underlying disease. However, its detection remains a critical step in medical evaluation, as early identification of associated health problems can facilitate timely treatment. Overall, understanding the overview of clubbing finger aids in recognizing its significance as a clinical sign and underscores the importance of comprehensive medical assessment.

Causes and Risk Factors Associated with Clubbing Finger

The development of clubbing finger is predominantly associated with chronic diseases that affect oxygenation and blood flow. Pulmonary conditions such as lung cancer, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, and interstitial lung diseases are among the most common causes. These illnesses often lead to prolonged hypoxia, which stimulates vascular and tissue changes in the fingertips. Cardiovascular diseases, including cyanotic congenital heart defects and infective endocarditis, are also significant contributors due to altered blood circulation and oxygen delivery. Recognizing these associations helps clinicians target appropriate investigations when clubbing is observed.

In addition to respiratory and cardiac conditions, gastrointestinal disorders can also lead to clubbing. Conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, and certain gastrointestinal cancers have been linked to the development of digital clubbing. The exact mechanisms remain unclear, but systemic inflammation and cytokine release are thought to play roles in tissue proliferation. Infectious diseases like tuberculosis and parasitic infections may also contribute, especially in endemic areas. These diverse causes highlight the importance of considering a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating a patient with clubbing.

Certain risk factors increase the likelihood of developing clubbing. Chronicity is a key element; long-standing illnesses are more likely to produce the characteristic physical changes. Smoking, environmental exposures, and genetic predispositions may also influence risk by exacerbating underlying conditions or affecting tissue response. Patients with a family history of congenital clubbing may be predisposed to develop the condition early in life. Additionally, immunocompromised states or recurrent infections can accelerate tissue changes in susceptible individuals. Awareness of these risk factors facilitates early detection and comprehensive management.

Lifestyle factors such as smoking and exposure to pollutants can worsen underlying lung diseases, indirectly increasing the risk of clubbing. Patients with occupational hazards involving inhaled toxins are also at higher risk of developing respiratory conditions associated with clubbing. Furthermore, comorbidities like diabetes or autoimmune disorders may complicate the clinical picture, making early diagnosis more challenging. Identifying these risk factors enables clinicians to monitor at-risk populations more closely and implement preventive strategies where possible.

Overall, the causes and risk factors for clubbing finger are multifaceted, involving a combination of chronic disease processes, environmental factors, and genetic predispositions. Understanding these elements is essential for clinicians to develop targeted diagnostic and management plans. Addressing modifiable risk factors, such as smoking cessation and reducing environmental exposures, can help decrease the incidence and severity of clubbing in susceptible individuals. Ultimately, comprehensive awareness of these causes enhances the clinician’s ability to provide timely and effective care.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Clubbing Finger in Patients

The primary symptom of clubbing finger is the visible enlargement and rounding of the fingertips. Patients or clinicians may notice that the tips of the fingers appear swollen, with the nails taking on a convex, curved shape. The angle between the nail bed and the nail itself, known as Lovibond’s angle, exceeds 180 degrees, creating a characteristic "clubbed" appearance. These physical changes are often painless but can be associated with discomfort or tenderness in some cases. Recognizing these signs promptly is crucial for early detection of underlying health issues.

In addition to physical appearance, patients may report symptoms related to their underlying disease, such as persistent cough, shortness of breath, fatigue, or chest pain, especially if the cause is respiratory or cardiac in origin. Some individuals might not experience any discomfort directly related to the clubbing itself, but the visible signs serve as an important clinical cue. Healthcare providers often perform specific tests like the Schamroth’s window test—placing the dorsal surfaces of the fingers together to observe the absence of a diamond-shaped window—to confirm the presence of clubbing. These assessments are simple, non-invasive, and effective in clinical settings.

Other associated signs include soft tissue swelling at the fingertips, increased curvature of the nails, and a loss of the normal nail bed angle. The nails may appear thickened or ridged, and the digital pulp may feel spongy or firm upon palpation. In advanced cases, the nail beds may become hyperplastic, further emphasizing the deformity. Patients might also experience nail bed hyperemia or redness, which can sometimes be mistaken for infection. Recognizing these symptoms early aids in differentiating clubbing from other nail or finger abnormalities.

Patients with long-standing underlying conditions may develop additional symptoms related to their primary disease, such as weight loss, fever, or respiratory distress. These systemic symptoms can help clinicians correlate the physical signs of clubbing with potential causes. It is essential to obtain a comprehensive history and conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish between benign and pathological causes of clubbing. Early recognition of symptoms ensures timely investigation and management of the underlying condition responsible for the clubbing.

In summary, the symptoms of clubbing finger are primarily observable through physical examination, with characteristic changes in the fingertips and nails. Recognizing these signs, coupled with patient history and systemic symptoms, enables healthcare providers to initiate appropriate diagnostic pathways. Awareness and prompt identification of clubbing symptoms are vital steps toward diagnosing potentially serious underlying diseases and improving patient outcomes.

The Role of Underlying Diseases in Clubbing Development

Clubbing finger is predominantly a manifestation of underlying systemic diseases, with the majority of cases linked to chronic conditions affecting the lungs and heart. Pulmonary diseases such as lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, and bronchiectasis are among the most common causes. These conditions often lead to hypoxia, which triggers vascular and tissue proliferation in the distal digits, resulting in the characteristic clubbing deformity. The severity of clubbing often correlates with the duration and extent of the underlying pulmonary pathology.

Cardiovascular diseases, particularly cyanotic congenital heart defects and infective endocarditis, also play a significant role in the development of clubbing. These conditions impair oxygen delivery to tissues, leading to chronic hypoxia that promotes tissue changes in the fingertips. The altered blood flow and oxygenation status serve as stimuli for vascular dilation and connective tissue proliferation, contributing to the physical changes observed in clubbing. Recognizing these links helps clinicians identify potential cardiac causes when evaluating patients with digital deformities.

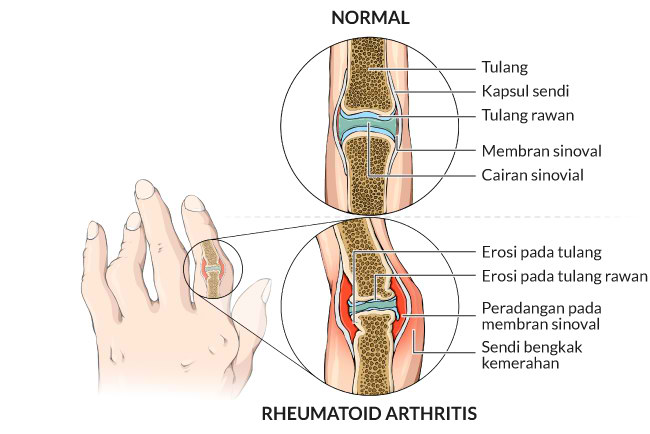

Gastrointestinal disorders are another important category associated with clubbing. Conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, and gastrointestinal malignancies have been implicated in the pathogenesis of digital clubbing. Although the mechanisms are not fully understood, systemic inflammation, cytokine release, and abnormal vascular responses are thought to contribute to tissue proliferation in the fingertips. These associations highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in diagnosing and managing patients with clubbing.

Infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis and parasitic infections, can also induce clubbing through chronic inflammatory processes. In endemic regions, these infections are notable causes of acquired clubbing, often in conjunction with other systemic symptoms. The persistent inflammatory response and tissue hypoxia in infectious states promote vascular and connective tissue changes, leading to the characteristic finger deformities. Understanding these infectious links is crucial for accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment.

Genetic and congenital factors can also influence the development of clubbing. Congenital syndromes such as primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (Pachydermoperiostosis) involve genetic mutations leading to early-onset clubbing and skin